Turn a blind eye or change course? Nelson’s demand-side reckoning.

If anyone deserved a break over the Christmas period, it was Tim Nelson and his fellow NEM review panellists.

In November 2024, Nelson and co. were given the noble (but arguably unenviable) task of recommending “future market settings to promote investment in firmed, renewable generation and storage capacity” in the NEM, and battling with the full spectrum of energy stakeholders (what weirdos!) in the process.

Different Nelson. Different battle. Different stakeholders.

The review is now complete and its final report - all 277 pages of it - was thumped on the desks of state and territory energy ministers as an early Christmas present. Queensland said “yeah… nah” but everyone else signed on in the most committal way you’d expect from a government minister one week before Christmas: “Sounds good in principle, now do some more work so I can delay thinking about this shit until after I’ve come back from Noosa.”

As is often the case with landmark NEM reviews, the focus of attention was on the supply side. And there are certainly supply-side problems worth resolving. Anyone even remotely interested in the news will have seen headlines about the challenges of building new transmission and bulk renewables at a reasonable cost and in a timeframe that will enable us to meet our renewable and emissions goals.

Nelson’s final report makes several recommendations on ways to support timely investment in supply side assets, and there has been considerable public commentary on them. In this post we’ll take a look at a less talked-about part of the report - the recommendations that relate to demand-side resources, including behind-the-meter batteries.

The problem

The key challenge identified by the Panel was that “the NEM is becoming a system that is more weather-dependent, more energy-constrained, less dispatchable, and less scheduled”.

With that context, here’s a summary of Nelson’s beef with the demand side:

There is a growing volume of spot price-responsive resources (e.g. batteries, flexible loads) being installed in the NEM.

Most of these resources are small and unscheduled, and so are not required to signal their operational intentions to the market like scheduled generators and loads are.

Consequently, demand-side resources operate however and whenever they like in response to spot prices - they are effectively “hidden” from AEMO.

This lack of visibility may mean that AEMO routinely over- or under-forecasts load, and consequently dispatches more or less than supply than is necessary, resulting in inefficient spot price outcomes and increased FCAS costs.

The paper notes that the demand side, particularly C&I users, already engages in several forms of flexibility, e.g. via spot-exposed retail contracts, offering RERT or providing FCAS. Nelson says that this is OK now, but will become a big problem if everyone gets a battery and starts being price-responsive.

Wholesale prices fluctuate like Oprah’s weight back in the day

The proposed solution

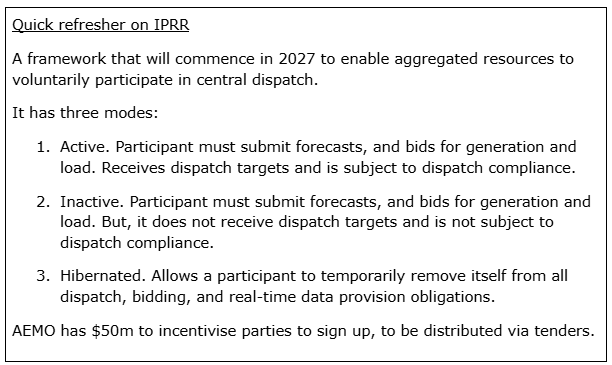

The final report concludes that the existing participation modes available in the market (IPRR, WDRM, scheduling) are not sufficiently flexible to cater to the full spectrum of price-responsive resources.

It recommends that AEMO develop a new “visibility-only” mode for certain resources, and that the IPRR framework be made mandatory for other resources above specified thresholds.

AEMO’s ISP team writing about how much wind we need even though nobody is building wind

To help guide AEMO’s thinking on this, the Nelson report recommends that:

Portfolios of batteries without co-located load that, in aggregate, exceed the 5MW registration threshold, must participate in IPRR dispatch mode (active) or register as a fully scheduled participant.

Portfolios of resources >30MW with co-located load that have automated control must participate in dispatch mode (inactive), with active dispatch mode remaining voluntary.

Large C&I loads with aggregate price-responsive load capacity >30MW must provide “load intention” data to AEMO via a new “visibility-only difference-bid” mode, or participate through the WDRM.

Retailers offering spot price pass-through contracts or price-contingent demand response contracts where aggregated price-responsive capacity is <30MW must submit quarterly reports to AEMO identifying all loads subject to such contracts.

The aim is for AEMO to have developed the framework by December 2026, with regulatory changes in place to enable implementation by 2030.

In recommending a mandatory approach, the Nelson panel has done what many stakeholders ultimately expected (and feared) would happen when the IPRR idea was first floated many years ago in a different NEM review process.

Nelson’s change in choice of who should drive the work is interesting, too. The draft report recommended that energy ministers submit a rule change request to the AEMC on the matter. The final report gives AEMO responsibility for developing the initial framework - so it’s natural to expect that AEMO will take Nelson’s endorsement of a mandatory approach and see how far they can ride it.

This may be the most high-brow set of references we’ve ever had.

The problem with the proposed solution

The paper accurately summarises all the reasons why C&I energy users don’t sign up for IPRR, or WDRM, or full market scheduling. The main reason is that energy market trading is not their core business but rather an opportunistic play if site operations allow it. The existing NEM design provides opportunities to benefit from spot price responsiveness without the implementation costs, technical challenges, compliance obligations, and potential penalties of the NEM’s scheduling and IPRR frameworks. Many of the demand flexibility business models and product innovations in the NEM today were created to capitalise on these opportunities. Such business models have succeeded because they can create value for customers through the combination of:

access to spot price incentives

low market participation costs

respecting the energy user’s energy autonomy by building flexibility actions around core business requirements

manageable compliance frameworks.

IPRR was developed in an attempt to get data from these sorts of players and keep participation costs low. But the model hasn’t actually been tested yet, and is kind of flawed. In a nutshell:

There is no obvious benefit to a small battery aggregator / VPP operator in participating in IPRR.

Mandating IPRR participation is broadly unpalatable and, given the operational and compliance costs, may negatively impact VPP and demand flexibility business cases.

Recognising this, the IPRR rule made participation voluntary. Given there’s zero benefit in signing up, the AEMC decided to throw money at it and run tenders to entice people to participate. That incentive framework hasn’t started yet, so who knows whether it’ll work? Nobody, that’s who..

If nobody signs up, AEMO won’t get the data or dispatchability it wants. Even if parties do sign up, the incentive framework will only support a smattering of price responsive portfolios in the NEM, so those resources that don’t sign up will still be hidden from AEMO.

The logical next step for a policymaker is to make IPRR mandatory and loosen some compliance obligations so people are forced to participate but aren’t so overwhelmed with the cost and complexity of participating that they leave the market altogether.

This is the line Nelson is trying to walk in the final report. Unfortunately, this approach creates two problems:

Mandatory approaches reduce the incentive to be price-responsive. Nelson has attempted to manage this risk with recommended capacity thresholds above which the obligations would kick in, but if AEMO pushes this much further in its detailed design then we risk disincentivising spot price responsiveness altogether, or creating perverse incentives to size portfolios right up to the threshold.

If the framework is too light-touch (e.g. if the new “visibility mode” involves no obligation for information provided to AEMO to be accurate) then the information received by AEMO is probably useless, rendering the whole exercise a dud.

It’s a wicked, cyclical problem and there’s no clear answer. But it does raise the question of how this review could have been used. Perhaps we could have explored solutions that didn’t involve IPRR and other mandatory modes? For example, ways to improve AEMO forecasting models to get a clearer picture of how price-responsive resources behave?

Let’s not forget…

In all the hype - good and bad - about VPPs, we often forget one thing: energy/wholesale arbitrage is one value stream in a stack of many others. C&I energy users are generally focused on three objectives when they get a battery:

reducing their reliance on grid electricity so they pay less in volumetric retail charges;

managing network costs better; and

delivering on their renewable/emissions goals by maximising onsite solar consumption.

A smart battery operator who respects their customer will prioritise delivery of these three value streams first, then seek to trade energy and other services if the opportunities arise and the benefits to the customer outweigh the costs.

Distributed batteries will not be trading their full capacity in the market every 5 minutes. That’s what scheduled batteries do because that’s their sole business purpose. So while the paper states that “distributed storage capacity could reach almost 6GW by 2030, equivalent to more than double the capacity of the Snowy 2.0 project”, it doesn’t recognise that the operational behaviour of the distributed storage capacity will be completely different to Snowy 2.0 - most of this distributed capacity will primarily be serving onsite load.

It’s not like engineers are known for catastrophising or anything.

Our take

One of the most interesting updates in AEMO’s recent draft ISP was that it recognised we could perhaps use the growing amount of capacity in our distribution networks to meet future reliability needs instead of building so much bulk generation and transmission.

In public policy, mandatory approaches tend to imply that there is a problem needing to be fixed. Unfortunately this is how several landmark NEM reviews have seen the demand side - a problem needing to be controlled rather than a huge opportunity that could be harnessed. While Nelson’s problem statement about the demand side isn’t entirely outrageous, the arguments are largely theoretical. They broadly imply that anyone controlling a battery will fire it off willy nilly with no foresight or forethought, with no other incentives of their own to consider.

This work isn’t over and we’ll see more papers on the matter before a solution is implemented. But we can all agree on one thing - batteries respond well to prices. If you get prices right - be it spot prices, network tariffs or retail prices - you create an incentive for the battery operator to do what you want it to do. And we all prefer carrots over sticks.